flowchart TD

%% Styling definitions

classDef start fill:#FFFACD,stroke:#FF8C00,stroke-width:2px,color:#000

classDef decision fill:#E6F3FF,stroke:#1E88E5,stroke-width:2px,color:#000

classDef correct fill:#E8F5E9,stroke:#43A047,stroke-width:2px,color:#000

classDef error fill:#FFEBEE,stroke:#E53935,stroke-width:2px,color:#000

%% Nodes

A([Start: Hypothesis Test]):::start

B{Reject H₀?}:::decision

C{H₀ True?}:::decision

D[Correct Decision<br/>True Negative<br/>1-α]:::correct

E[Type II Error<br/>False Negative<br/>β]:::error

F[Type I Error<br/>False Positive<br/>α]:::error

G[Correct Decision<br/>True Positive<br/>1-β]:::correct

%% Flow connections

A --> B

B -->|No| C

B -->|Yes| C

C -->|Yes| D

C -->|No| E

C -->|Yes| F

C -->|No| G

Day 32

Math 216: Statistical Thinking

How Statistical Decisions Can Go Wrong

Key Question: What happens when our statistical conclusions are wrong? Understanding Type I and Type II errors helps us make better decisions and design more effective studies!

The Two Types of Statistical Mistakes:

Type I Error (\(\alpha\)): False alarm! Rejecting \(H_0\) when it’s actually true \[\alpha = P(\text{Reject } H_0 \mid H_0 \text{ true})\]

Type II Error (\(\beta\)): Missed opportunity! Failing to reject \(H_0\) when \(H_a\) is true \[\beta(\mu) = P(\text{Fail to reject } H_0 \mid \mu = \mu_a)\]

Power (\(1-\beta\)): Getting it right! Correctly detecting real effects \[\text{Power}(\mu) = 1 - \beta(\mu) = P(\text{Reject } H_0 \mid \mu = \mu_a)\]

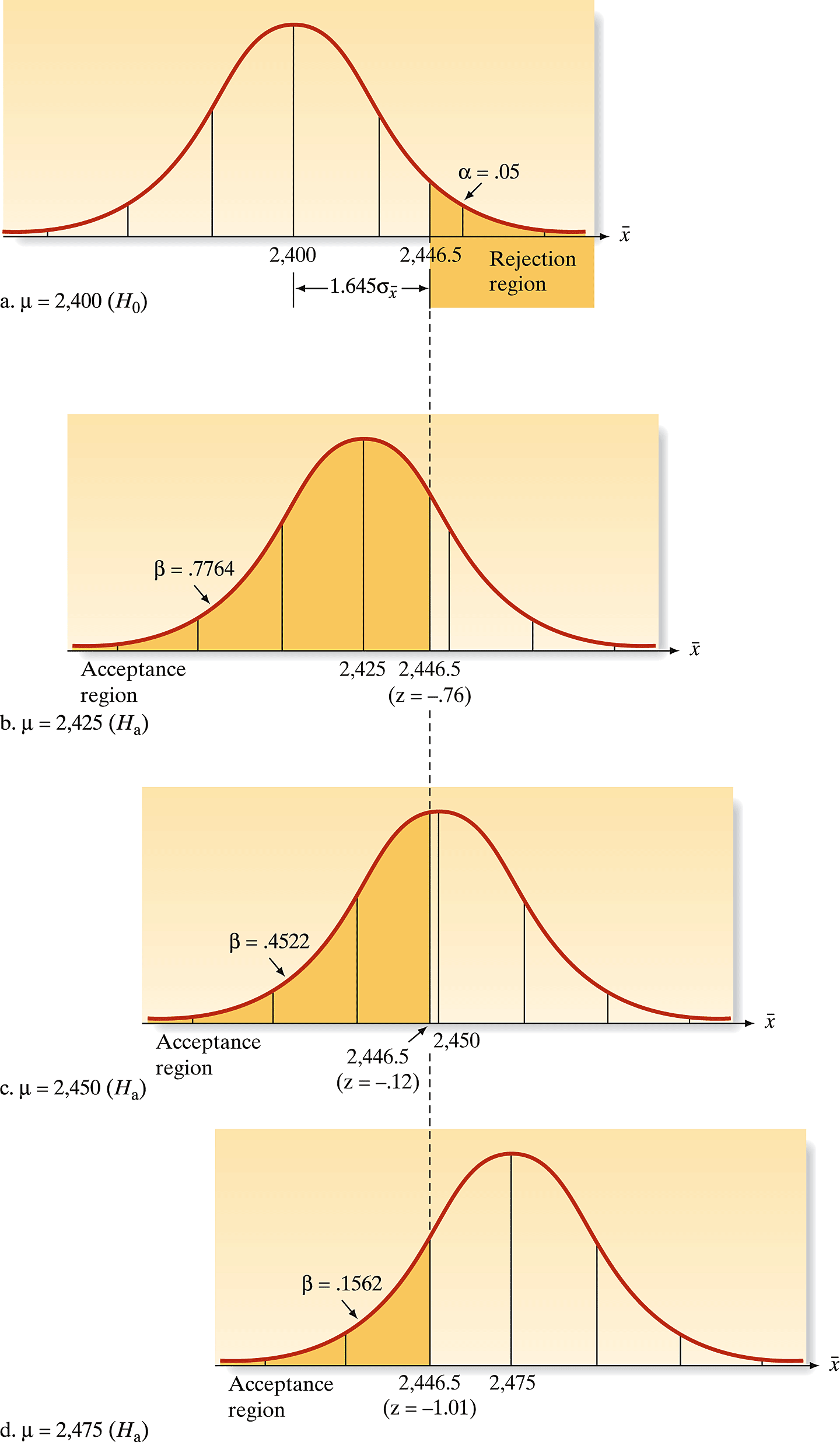

Hypothesis Testing Errors

Real-World Example: Quality Control Testing

Manufacturing Scenario: Testing if new production process increases product strength

Null Hypothesis (\(H_0\)): No improvement in strength (\(\mu = 2400\))

Alternative Hypothesis (\(H_a\)): Process increases strength (\(\mu > 2400\))

Test Statistic: \[ z = \frac{\bar{x} - 2400}{\sigma / \sqrt{n}} \]

Standard Error: \(\sigma_{\bar{x}} = 28.267\) (based on historical data)

Rejection Region: For \(\alpha = 0.05\), reject \(H_0\) if \(z > 1.645\)

What We’re Testing: Is the observed improvement real, or just random variation?

Visualizing Error Probabilities

Understanding the Trade-off:

- Red Area (\(\alpha\)): The 5% chance of a false alarm - rejecting \(H_0\) when it’s actually true

- Type II Error (\(\beta\)): The risk of missing a real effect when \(H_a\) is true

- Power (\(1-\beta\)): Our ability to detect real improvements

Key Insight: As the true mean moves farther from \(2400\), our power increases and \(\beta\) decreases - we’re more likely to detect real improvements!

Calculating Type II Error Risk

When \(H_0\) is False: What’s our risk of missing the real effect?

- Type II Error (\(\beta\)): Probability of not rejecting \(H_0\) when it’s actually false

- Depends on: How far the true mean is from the null value

Example Calculation: If the true mean is 2425 (slight improvement)

\[ \beta = \operatorname{Prob}\left[\bar{x} < 2446.5 \mid \mu = 2425\right] = 0.7764 \]

Interpretation: We have a 77.6% chance of missing this small improvement! This shows why small effects are hard to detect.

Statistical Power: Getting It Right!

Power = 1 - \(\beta\): Our ability to detect real effects when they exist

- High Power: Good at finding real improvements

- Low Power: Often misses real effects

Why Power Matters:

- Medical Research: Need high power to detect treatment benefits

- Quality Control: Need balanced power to avoid false alarms

- Scientific Studies: Underpowered studies waste resources

Key Insight: Power increases as effects get larger and samples get bigger!

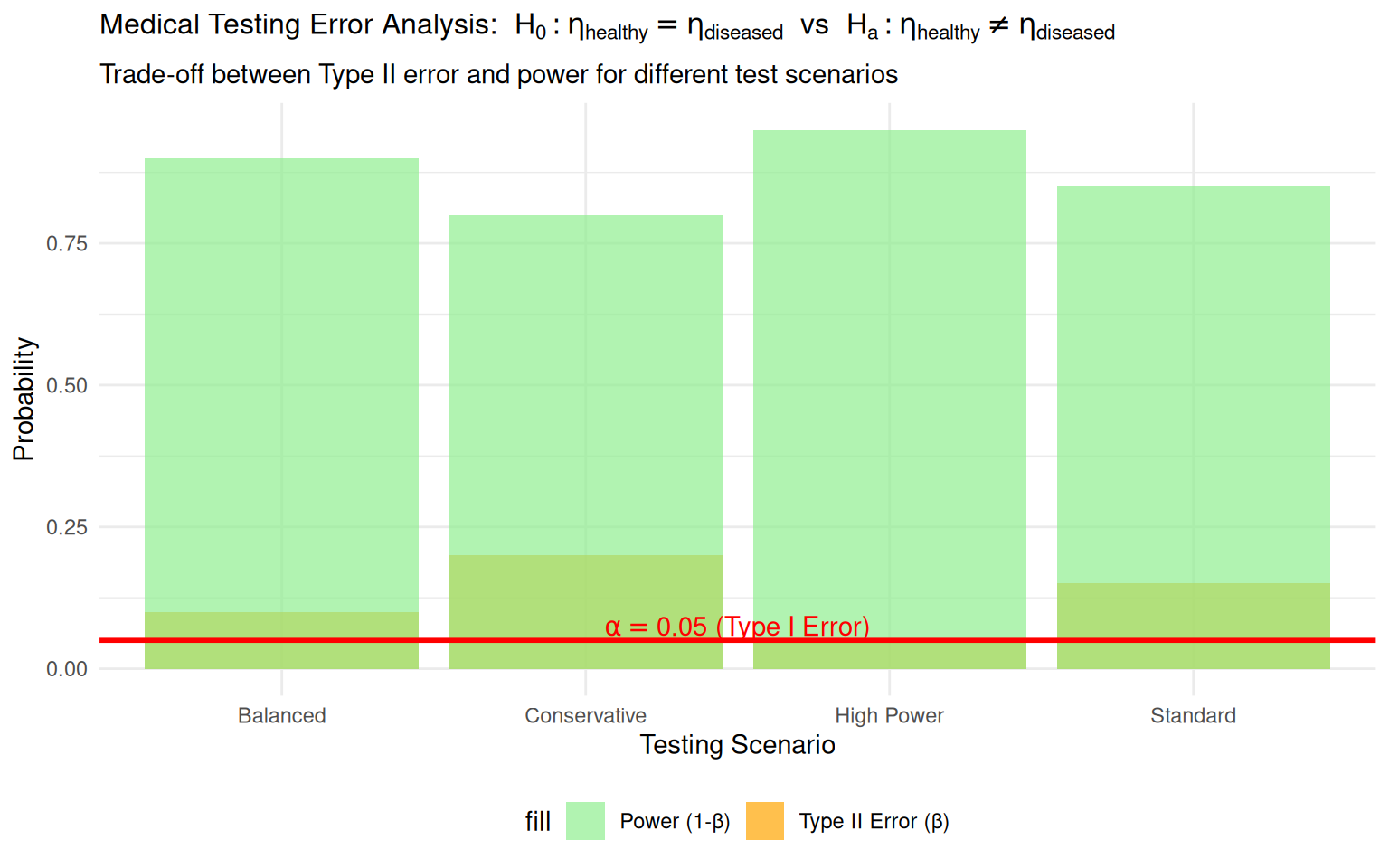

Worked Example 1: Medical Testing Error Analysis

Context: Medical diagnostic test with known error rates

Worked Example 1: Formal Hypothesis Test Setup

- \(H_0\): Patient is healthy (no disease present)

- \(H_a\): Patient has disease (medical condition present)

- Type I Error (\(\alpha\)): False positive (healthy patient diagnosed as diseased)

- Type II Error (\(\beta\)): False negative (diseased patient diagnosed as healthy)

- Power (\(1-\beta\)): Correctly detecting disease when present

Error Probability Calculations:

- Scenario 1 (Conservative): \(\alpha = 0.05\), \(\beta = 0.20\), Power = 0.80

- Scenario 2 (Standard): \(\alpha = 0.05\), \(\beta = 0.15\), Power = 0.85

- Scenario 3 (Balanced): \(\alpha = 0.05\), \(\beta = 0.10\), Power = 0.90

- Scenario 4 (High Power): \(\alpha = 0.05\), \(\beta = 0.05\), Power = 0.95

Interpretation:

- Lower \(\beta\) values increase power but may require more sensitive tests

- Medical context often prioritizes minimizing \(\beta\) (false negatives)

- Trade-off between sensitivity and specificity

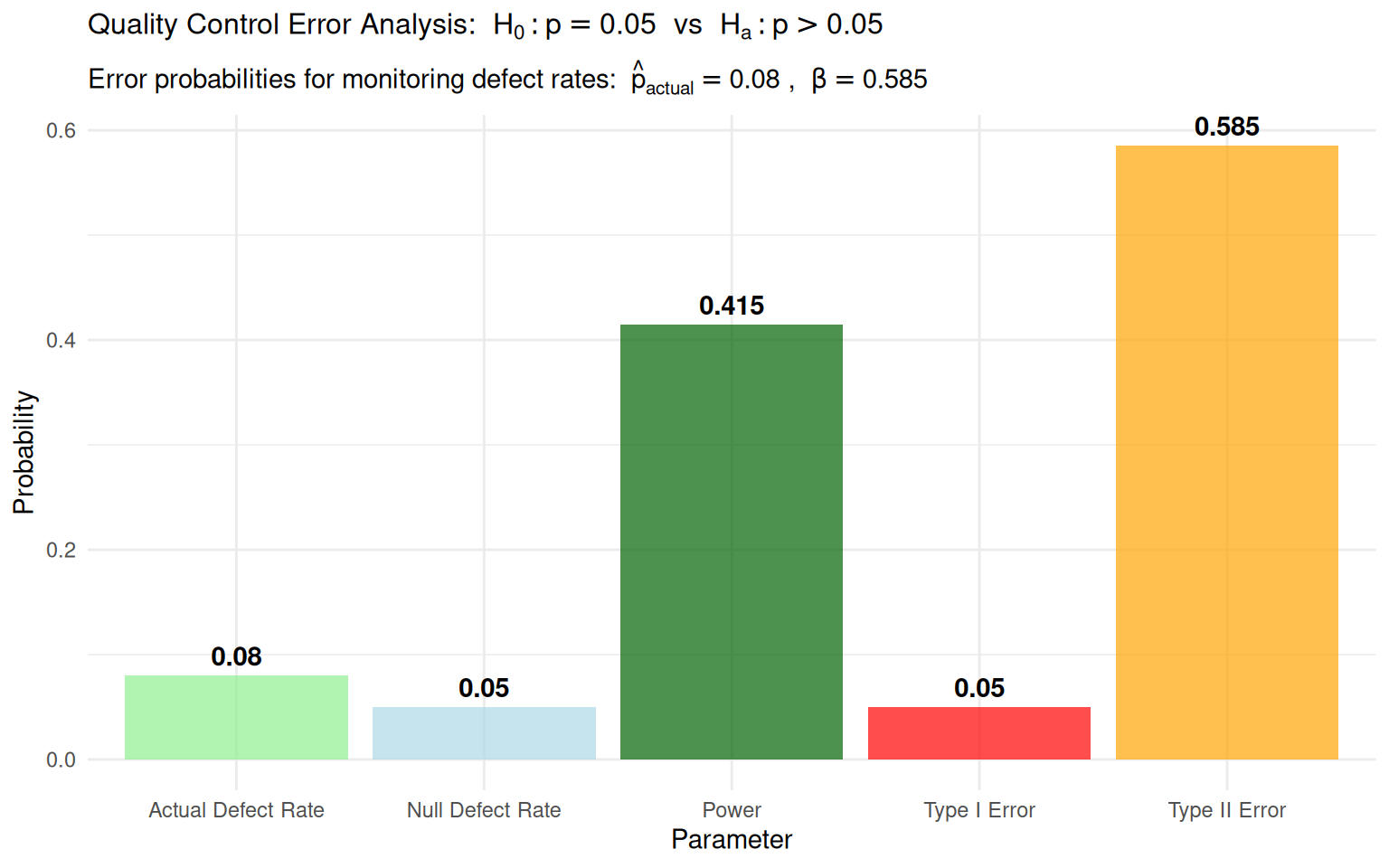

Worked Example 2: Quality Control Error Analysis

Context: Manufacturing process monitoring for defect rates

Worked Example 2: Formal Hypothesis Test Setup

- \(H_0\): \(p = 0.05\) (process operating at acceptable defect rate)

- \(H_a\): \(p > 0.05\) (process producing excessive defects)

- Sample: n=100 items monitored

- Rejection Region: \(\hat{p} > 0.05 + 1.645\sqrt{0.05(0.95)/100}\)

Error Probability Calculations:

Type I Error (\(\alpha\)): Probability of rejecting \(H_0\) when process is acceptable \[\alpha = 0.05\]

Type II Error (\(\beta\)): Probability of accepting \(H_0\) when actual defect rate is 8% \[\beta = P(\hat{p} < 0.0858 \mid p = 0.08) = 0.585\]

Power (\(1-\beta\)): Probability of detecting process deterioration \[\text{Power} = 1 - 0.585 = 0.415\]

Practical Implications:

- Current test has only 41.5% chance of detecting 8% defect rate

- May need larger sample size or lower \(\alpha\) for better detection

- Quality control requires balancing error rates with monitoring costs

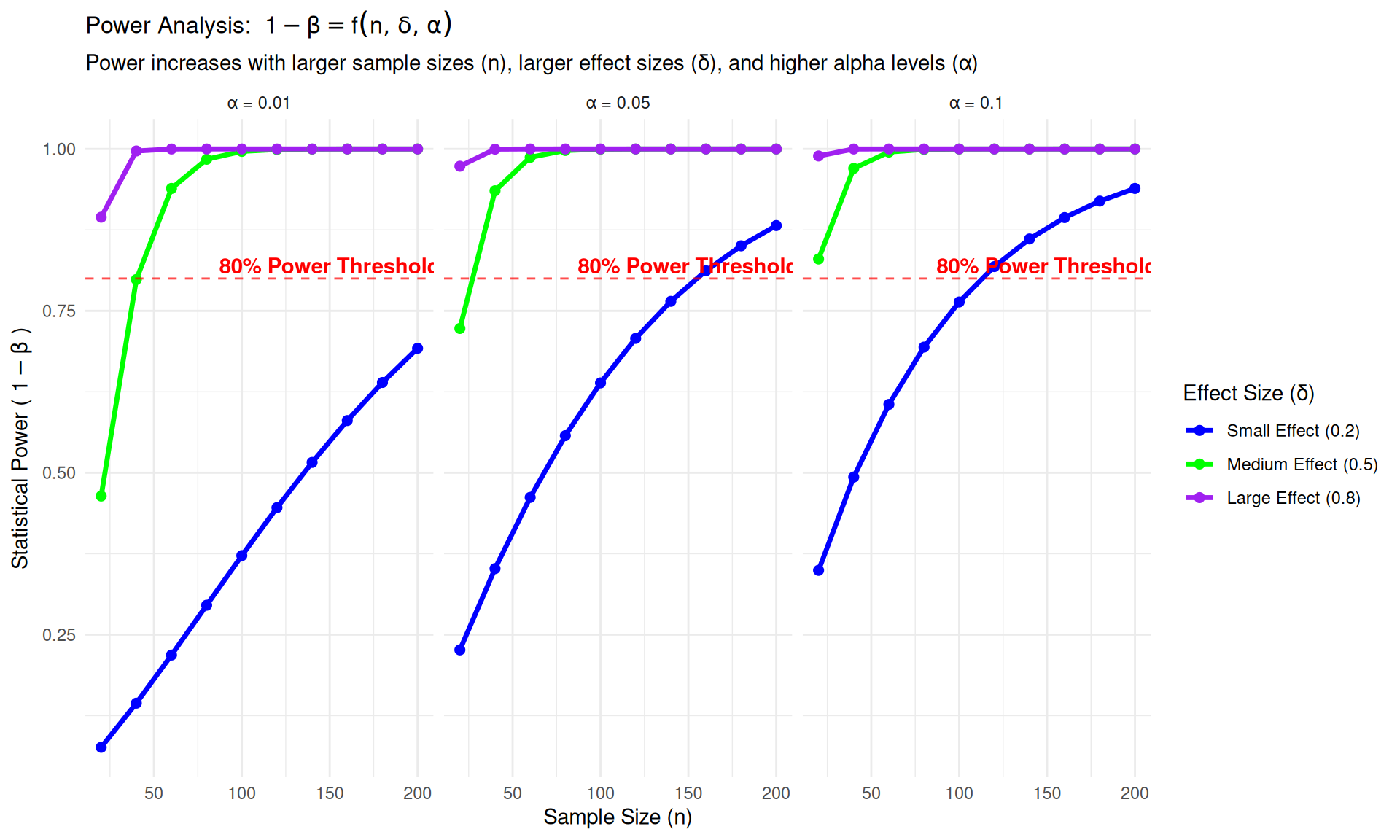

What Determines Statistical Power?

Effect Size (\(\delta\)): How big is the real difference? \[\delta = |\mu_a - \mu_0|\]

- Large effects: Easy to detect (high power)

- Small effects: Hard to detect (low power)

Sample Size (\(n\)): How many observations do we have?

- Large samples: More precise estimates (high power)

- Small samples: More uncertainty (low power)

Significance Level (\(\alpha\)): How strict are we about false alarms?

- Conservative (\(\alpha=0.01\)): Fewer false alarms, lower power

- Liberal (\(\alpha=0.10\)): More false alarms, higher power

Population Variability (\(\sigma\)): How noisy is our data?

- Low variability: Clear signal (high power)

- High variability: Hard to see signal (low power)

Power Analysis Visualization

Practical Power Analysis: Planning Better Studies

# How much power do I have with n=30?

power.t.test(n = 30, delta = 0.5, sd = 1, sig.level = 0.05, type = "one.sample")

One-sample t test power calculation

n = 30

delta = 0.5

sd = 1

sig.level = 0.05

power = 0.7539627

alternative = two.sided# How many subjects do I need for 80% power?

power.t.test(power = 0.80, delta = 0.5, sd = 1, sig.level = 0.05, type = "one.sample")

One-sample t test power calculation

n = 33.3672

delta = 0.5

sd = 1

sig.level = 0.05

power = 0.8

alternative = two.sidedReal-World Interpretation:

“Our study with 30 participants has 80% power to detect a medium effect. This means if the treatment really works, we have an 80% chance of finding it.”